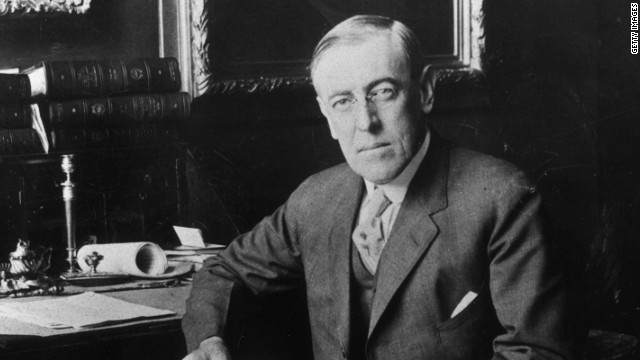

moulddni0.com – Woodrow Wilson, the 28th president of the United States, led the country during one of the most tumultuous and transformative periods in modern history. From 1913 to 1921, Wilson’s presidency was shaped by profound challenges, both domestic and international. Most notably, the United States entered World War I in 1917, a conflict that would leave deep scars on both Europe and America. Wilson’s leadership during the war, his efforts to shape the postwar world, and his domestic reforms during this era had a lasting impact on the United States and the international community.

In the shadow of World War I, Wilson’s leadership was characterized by a complex blend of idealism and pragmatism, optimism and disappointment. His vision of a world reshaped by democratic ideals and collective security came to fruition in the creation of the League of Nations, but his failure to secure American participation in this international institution was a significant blow to his presidency. On the domestic front, Wilson’s reforms focused on progressive economic policies, social justice, and government regulation, but his presidency was also marked by contentious issues, including racial segregation and his responses to labor unrest.

This article will explore the multifaceted nature of Woodrow Wilson’s leadership during World War I, examining how his presidency both reflected and responded to the challenges of the war, the postwar peace process, and his vision for a new world order. It will also delve into the contradictions of his presidency, exploring the idealism that defined his foreign policy and the domestic realities that limited his accomplishments.

Wilson’s Leadership During World War I

Neutrality and the Path to War

When Wilson assumed the presidency in 1913, he faced a world that was on the brink of war. Europe was dominated by alliances and tensions between major powers, and the militarization of Europe was well underway. Despite the growing instability, Wilson’s initial stance was one of neutrality. Wilson, a scholar of political philosophy and history, was deeply committed to the idea that the United States should avoid foreign entanglements. His early foreign policy, which he termed “moral diplomacy,” was focused on promoting democracy and human rights while steering clear of unnecessary conflicts.

For much of his first term, Wilson adhered to a policy of neutrality, even as the war in Europe escalated. The outbreak of World War I in 1914, with its devastating consequences, tested Wilson’s resolve. While the United States remained formally neutral, the conflict had significant economic implications. American businesses began trading with the Allies, and the country’s financial ties to Europe deepened. This created a complicated situation for Wilson, who was under pressure from both pro-Allied factions and those who wished to avoid involvement.

In 1915, the German policy of unrestricted submarine warfare against ships, including civilian vessels like the Lusitania, led to the deaths of American citizens. This event intensified the debate over U.S. involvement in the war. However, Wilson initially resisted calls for war, preferring diplomatic measures to ensure the safety of American lives and commerce.

The Decision to Enter the War

Wilson’s commitment to neutrality faced its breaking point in early 1917, when Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, targeting any and all ships, including American merchant vessels. Additionally, the Zimmermann Telegram, in which Germany promised Mexico territorial gains in exchange for an alliance against the U.S., further inflamed public opinion. In April 1917, Wilson went before Congress to ask for a declaration of war, famously stating that the world must be made “safe for democracy.”

His decision to enter the war was driven by a belief that the United States had a moral duty to fight for global democracy and against autocratic powers like Germany. Wilson framed the war as not just a struggle between nations, but as a battle for the preservation of the ideals of self-government and liberty. His message was clear: the United States was not entering the war for imperial conquest or national gain but to protect democratic values across the globe.

Mobilizing for War

Once the United States entered the war, Wilson faced the daunting task of mobilizing the nation for a conflict that was already well underway. Wilson, as a leader, was keenly aware that the war required not only military preparedness but also the full commitment of the American people. He established the War Industries Board (WIB) to oversee the production of war materials and the Selective Service Act to implement a military draft. Wilson also worked with labor unions to ensure that the war effort did not face internal disruptions from strikes or other labor actions. At the same time, the U.S. government took unprecedented steps to control the economy, ration essential goods, and regulate industries involved in the war effort.

Wilson’s leadership during the war required him to balance military strategy with economic and social stability. His administration had to ensure that the American public stayed united and focused on the war effort, which proved to be a significant challenge in a country that had entered the war with reluctance. In this respect, Wilson’s rhetorical ability and commitment to democratic ideals helped him to rally the American people around the war effort, even as the loss of life mounted.

The American Expeditionary Forces and the End of the War

Under Wilson’s leadership, the United States sent over 2 million American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) to Europe. Led by General John J. Pershing, the AEF played a critical role in tipping the balance of the war in favor of the Allies. While the United States did not enter the conflict until 1917, the fresh troops and supplies that arrived in Europe helped to break the stalemate on the Western Front. By the end of 1918, the Central Powers were in retreat, and an armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, bringing an end to the fighting.

Despite the end of hostilities, Wilson’s leadership was not yet complete. He embarked on an ambitious mission to shape the postwar world through the Treaty of Versailles and his plan for a new international organization—the League of Nations.

Wilson’s Vision for a Postwar World: The League of Nations and the Fourteen Points

The Fourteen Points: A Vision of Global Democracy

Wilson’s vision for a postwar world was grounded in his belief in self-determination, democracy, and international cooperation. In January 1918, long before the war ended, Wilson outlined his Fourteen Points, a blueprint for peace that would guide the negotiations following the conflict. The Fourteen Points called for open diplomacy, freedom of the seas, the reduction of armaments, the self-determination of nations, and the establishment of a League of Nations to promote peace and prevent future wars.

Wilson’s idealistic vision of a peaceful world order stood in stark contrast to the more punitive approaches that many of the European Allies favored. Wilson’s points emphasized diplomacy over territorial conquest, with a focus on promoting justice and fairness in the aftermath of the war. His goal was not only to end the war but also to create a framework that would prevent the rise of future conflicts and encourage the peaceful resolution of disputes.

The Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Wilson worked tirelessly to secure the adoption of his Fourteen Points, particularly his vision of the League of Nations. The League was to serve as an international body where nations could resolve disputes, collaborate on global issues, and, if necessary, take collective action to preserve peace. Wilson believed that the League was essential for maintaining a stable world order and preventing future wars.

However, the other Allied powers, particularly Great Britain and France, were less inclined to accept Wilson’s idealism. They were more focused on punishing Germany for the war and securing reparations to rebuild their devastated economies. As a result, the Treaty of Versailles that emerged from the negotiations was far more punitive than Wilson had hoped. It imposed harsh penalties on Germany, including heavy reparations and territorial losses, which Wilson opposed. Nevertheless, he compromised, believing that the establishment of the League of Nations was worth the price.

The Treaty of Versailles, which formally ended World War I, included the creation of the League of Nations as well as provisions for the self-determination of nations and the redrawing of borders in Europe. Wilson returned to the United States in 1919, hoping to gain support for the treaty and the League. However, he faced fierce opposition in the U.S. Senate, where isolationist and Republican senators refused to ratify the treaty.

The Senate’s Rejection and Wilson’s Legacy

Wilson’s failure to secure U.S. participation in the League of Nations was one of the greatest disappointments of his presidency. Despite his personal commitment to the idea of a collective security arrangement, the American public and political establishment were not ready to fully embrace the internationalist vision he had championed. The Senate’s rejection of the Treaty of Versailles meant that the United States did not join the League of Nations, undermining Wilson’s efforts to create a new world order based on peace and diplomacy.

Wilson’s health also deteriorated after the failure of the League. In 1919, he suffered a debilitating stroke that left him physically weakened and unable to effectively lead the country. His second term in office, which began in 1917, was marred by his inability to recover from the stroke, and his presidency ended in political paralysis.

Conclusion: Woodrow Wilson’s Leadership in the Shadow of World War I

Woodrow Wilson’s leadership during World War I and the subsequent peace process was a defining moment in American history. His idealistic vision for a world based on democracy, self-determination, and collective security laid the foundation for modern international relations, even if that vision was never fully realized during his lifetime. Wilson’s leadership during the war demonstrated his ability to navigate complex political and military challenges, while his efforts to shape the postwar world through the League of Nations reflected his belief in the power of diplomacy and international cooperation.

At the same time, Wilson’s presidency was marked by contradictions. His progressive domestic policies, aimed at reducing inequality and promoting social justice, were often undermined by his failure to address racial issues and his inability to effectively deal with labor unrest. His commitment to democratic ideals was also tempered by the limitations of his idealism in the face of realpolitik and the isolationist tendencies of the American political system.

In the shadow of World War I, Wilson’s leadership was both visionary and flawed. His failure to secure American participation in the League of Nations and his inability to fully implement his idealistic postwar vision were significant setbacks. Yet his legacy endures in the principles of international cooperation and the idea that nations can work together to prevent future wars. Wilson’s presidency, defined by its triumphs and disappointments, serves as a reminder of the complexities of leadership in times of crisis and the enduring tension between idealism and reality.